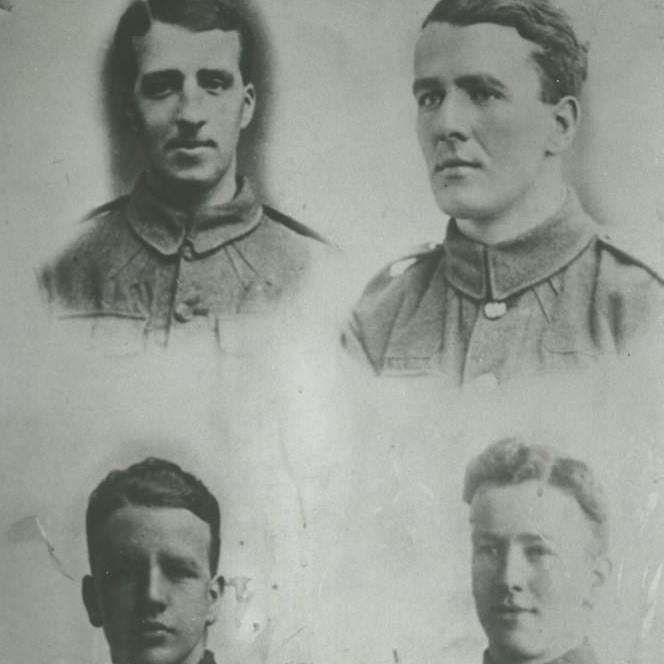

This flash fiction sketch is inspired by a true story. This is a picture of my grandfather [lower left] and his three brothers. They fought in WWI. The story is that they all got leave at the same time for one holiday, which was unusual, and they rode horses quite a distance to meet up in France. The miraculous part of the story is all four brothers survived the war. So much of the story is lost so that’s why this is ‘inspired by a true story’ and not creative non-fiction. We don’t know if it was Christmas, or some other holiday. We don’t know exactly where they met. We do know their names. I know that my grandfather Johnny was a tailor, and the jobs of his other brothers were recorded in family documents. I did a little research about trench foot and what a menace it was for the men fighting. It is strange to think that fresh socks were a factor in winning the war. I also read some articles about the heroism of horses in the war, and the tragedy of how many were lost. The amount of research it takes to write an accurate war story is staggering, so that’s why I call this just a humble sketch.

Johnny held the telegram in one hand and the sock he was mending in the other. He crouched in the trench with a cigarette dangling from his lip. He thought the telegram would say one of his brothers was dead.

But the telegram said his three brothers were alive and well.

Johnny never guessed he’d be a hero for mending socks. It turned out saving men from the terror of trench foot was more important than putting bullets into Germans.

“We’ve got another bag for ya, Johnny!” Harris said, tossing a duffel to him. There must have been two hundred pairs of socks in this bag. He was lucky when he found a pair that weren’t bloody. He’d mend the socks, lay them out in the sun to dry, and try not to think about the last pair of feet that were in them.

His brothers were alive and well and still walking in their own socks, thankfully. The telegram read: Meet in Paris on leave. Jan 1?

Johnny was the youngest of the brothers at age twenty. Two years at war had stripped all meaning of being the youngest or the oldest or even a man. The eighteen-year-old from Strathaven, Scotland was hardly there anymore. But when he thought of his brothers, he felt like himself. His heavy heart would grow light for a moment.

How was he going to get across France to see them?

“Take Howie, okay, Johnny? She’s in bad shape and can’t pull artillery anymore, anyway,” Harris said.

Johnny rode Howie the horse — short for Howitzer — day and parts of the night. He slept in the ditch a few hours at a time, and took it slow so the horse would last. It was a dangerous journey, but still safer than the trenches. The days riding through the French countryside with Howie were a world away from the bags of bloody broken socks, belying the numbers of bloody broken men.

The road was long, but Johnny did make it to the little French tavern on the outskirts of Paris. He tied Howie to a tree nearby, gave her neck a scratch, and headed inside. Despite the low kerosene glow of the rustic little bar, he saw William and James right away lounging at a table with two bottles of wine gone already. They jumped up from the wood table when they saw Johnny.

“You’re alive!” They hugged him roughly.

“Another bottle of wine!” William demanded. “Our little brother is still alive!” The bar patrons — mostly old men, and a few young, beautiful women — roared happily at the news.

While Johnny was a tailor, William’s job was inspecting communication lines. James had fought at the front, but a grenade blew off part of his left hand.

“That’s okay. I don’t fight anymore. I take care of the horses, now,” James said, his injured arm tucked closely to his side.

His brothers’ eyes looked haunted. But the more they talked about old times, the more the ghosts of war retreated. The brothers were just the boys from Strathaven once again.

Johnny tried not to think about Guy, who wasn’t here yet. Guy was the most dashing of the brothers. He drove a munitions truck and they all knew it was dangerous.

Johnny, William, and James started to sing, like they always did when they were full of spirits and spirit. They sang Annie Laurie. The bar fell silent listening to them. The boys could really sing.

They were almost at the end when another voice joined in:

Her voice is low and sweet

And she’s a’ the world to me

And for bonnie Annie Laurie

I’d lay me down and dee.

Guy’s baritone finished the song. Everyone in the bar cheered again.

Guy gruffly hugged them all and said, “How about a wee dram?” They toasted one last time.

Johnny woke again in the trenches. A bag of bloody socks still lay beside him. But it was awhile before the sad refrain of Annie Laurie faded.